RCPSP

River Lot 909

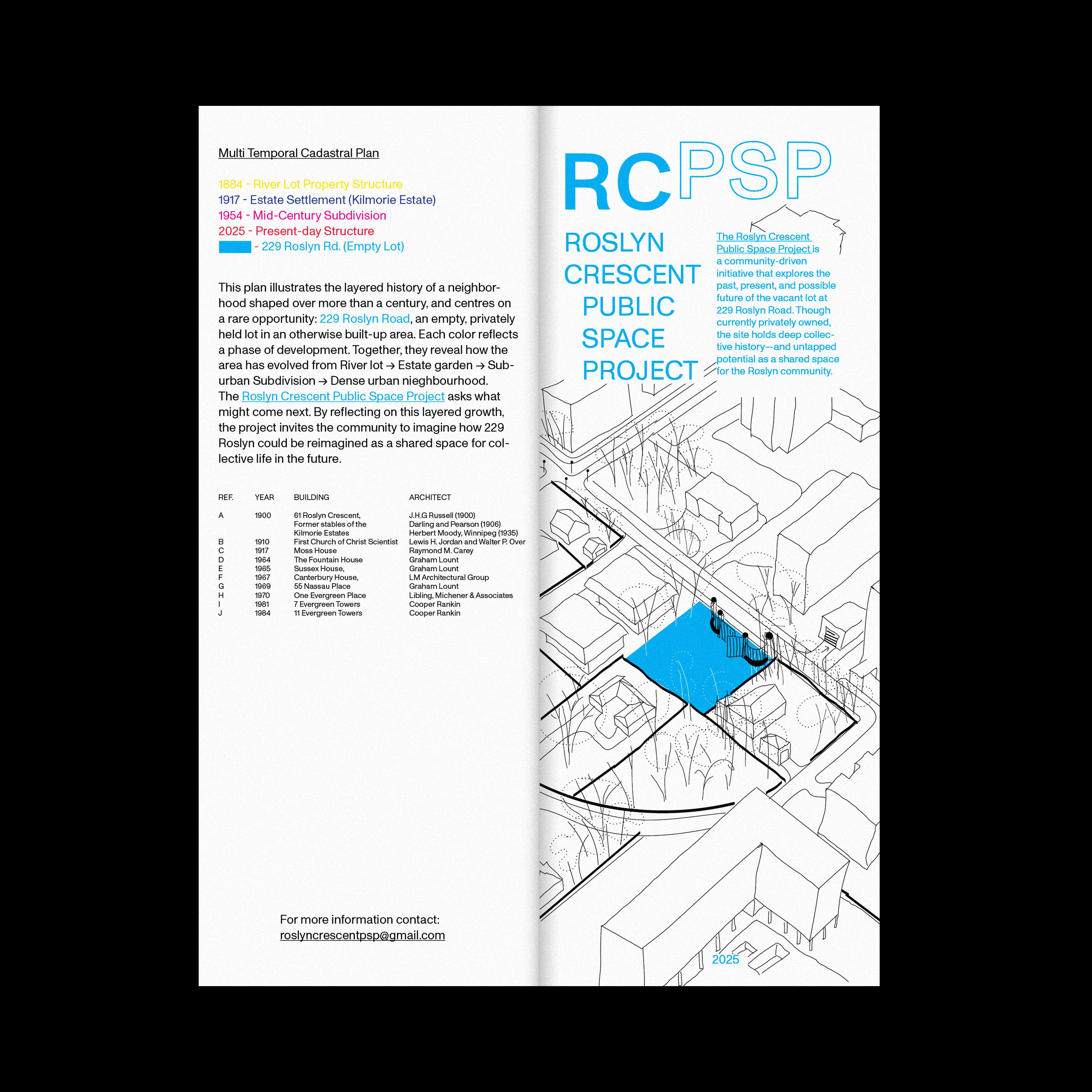

This project investigates the layered history of Lot 909—now Roslyn Crescent—in Winnipeg’s Osborne neighborhood. Drawing from archival maps, land surveys, development records, and ecological data, the research documents how the site has shifted from floodplain bushland to elite estate grounds, to postwar suburb, and finally to dense urban neighbourhood. Through close analysis of these transformations, the project highlights how land management, urban infrastructure, and environmental intervention have shaped both the identity and function of this riverfront site.

River lot → Estate → Garden → Subdivision → Urban Growth → Empty Lot → ?

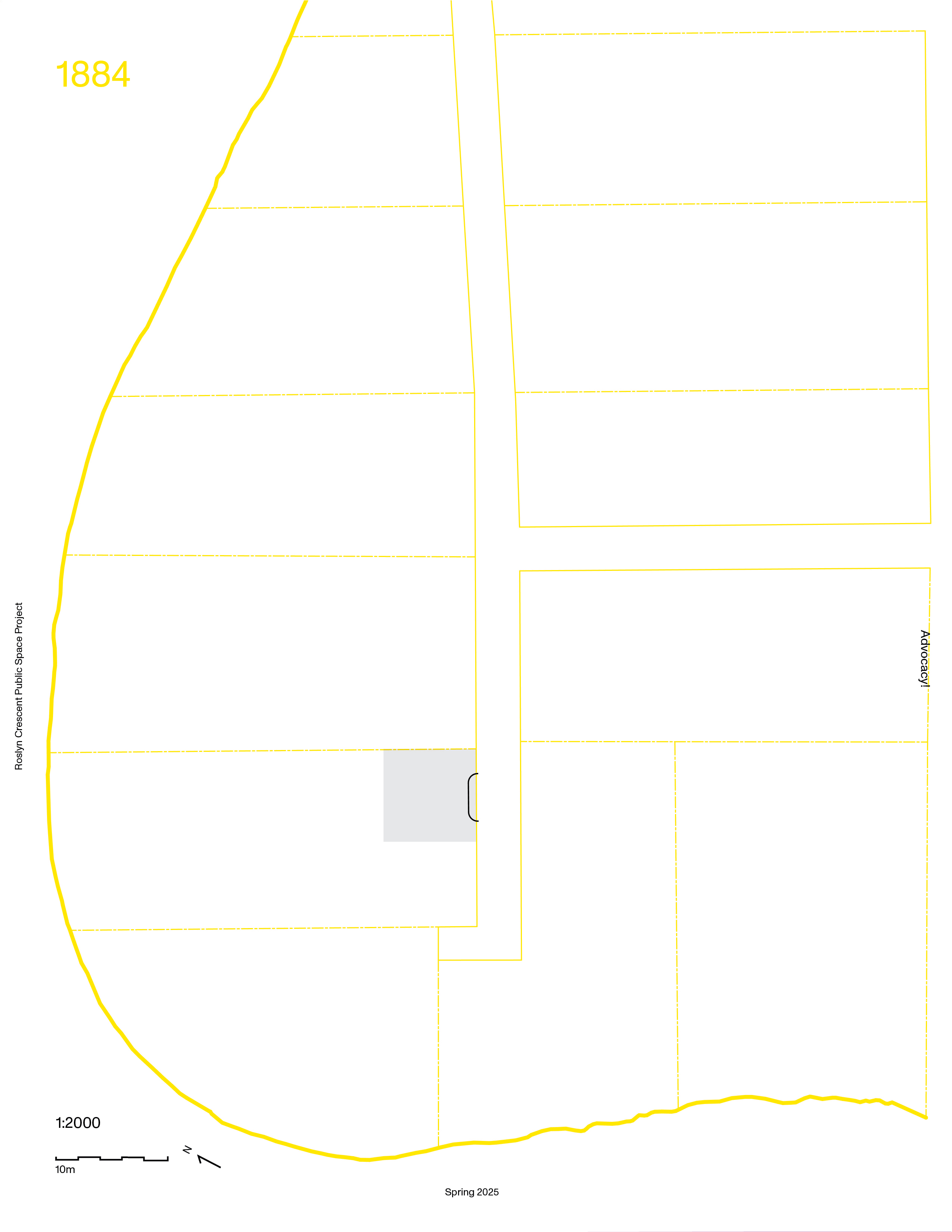

RIVER LOT (Lot 909)

The Land was designated as Lot 909 by the Hudson’s Bay Company. It formed part of the Red River’s river lot system, which divided land into long, narrow allotments to ensure each property had direct access to both the river and the road. This arrangement offered vital connections for transportation and communication—essentially granting each lot access to the region’s “superhighway.” The southern boundary of the property is defined by this historic river lot system. Its crescent shape follows the natural curve of the Assiniboine River, which establishes the western and northern edges. The eastern boundary aligns with present-day Osborne Street, which separates HBC Lots 908 and 909.

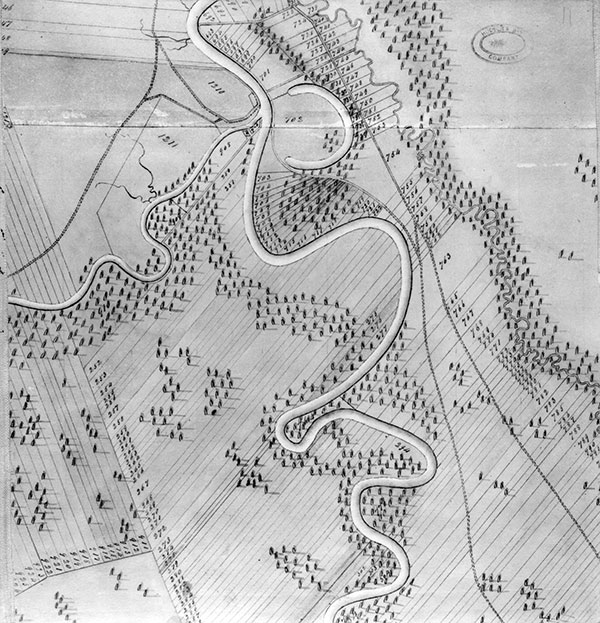

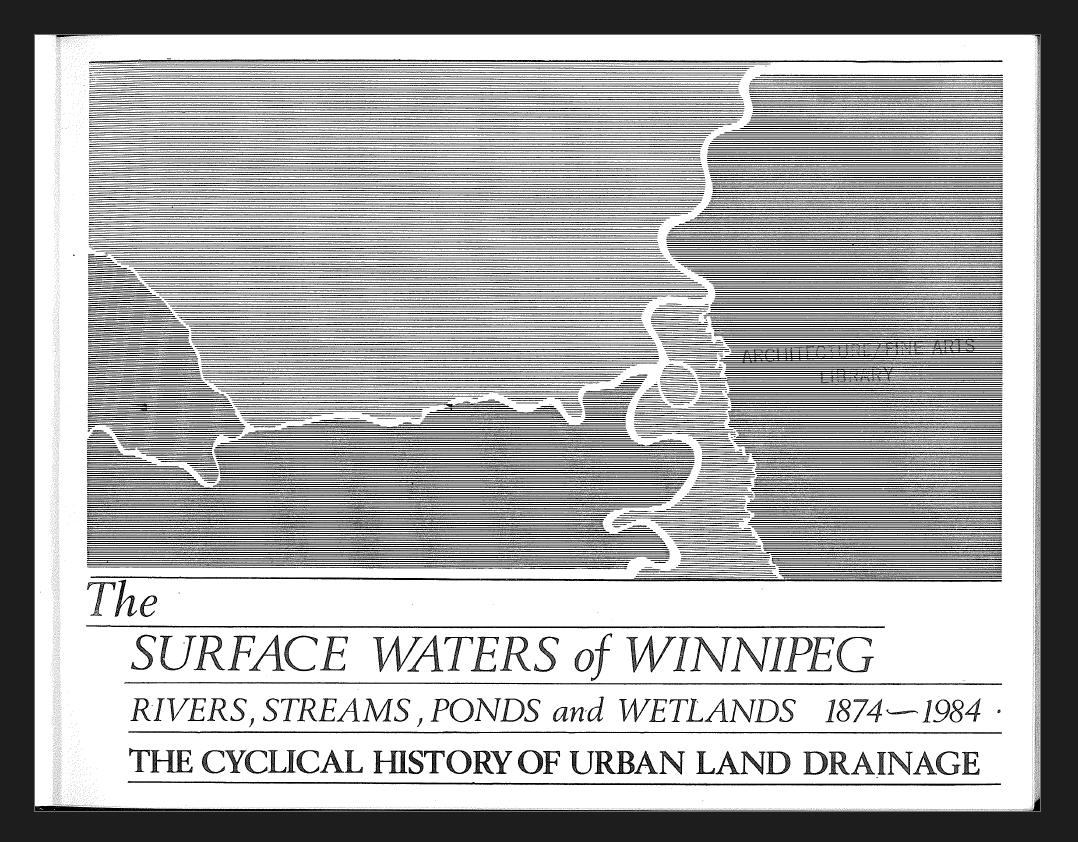

The Plan of the Settlement on Red River as it was in June 1816 was published in 1898. The Land at that time was described as “woods interspersed with small prairies extending for miles.” It was likely densely treed—maple, elm, willow, and cottonwood along the flood zone, with oak and prairie grasses above the floodplain. This was the mucky, swollen clay soil of Fort Rouge—flood-prone bushland shaped by the river’s rhythm.

The Plan of the Settlement on Red River as it was in June 1816 was published in 1898. The Land at that time was described as “woods interspersed with small prairies extending for miles.” It was likely densely treed—maple, elm, willow, and cottonwood along the flood zone, with oak and prairie grasses above the floodplain. This was the mucky, swollen clay soil of Fort Rouge—flood-prone bushland shaped by the river’s rhythm.

The Plan of the Settlement on Red River as it was in June 1816

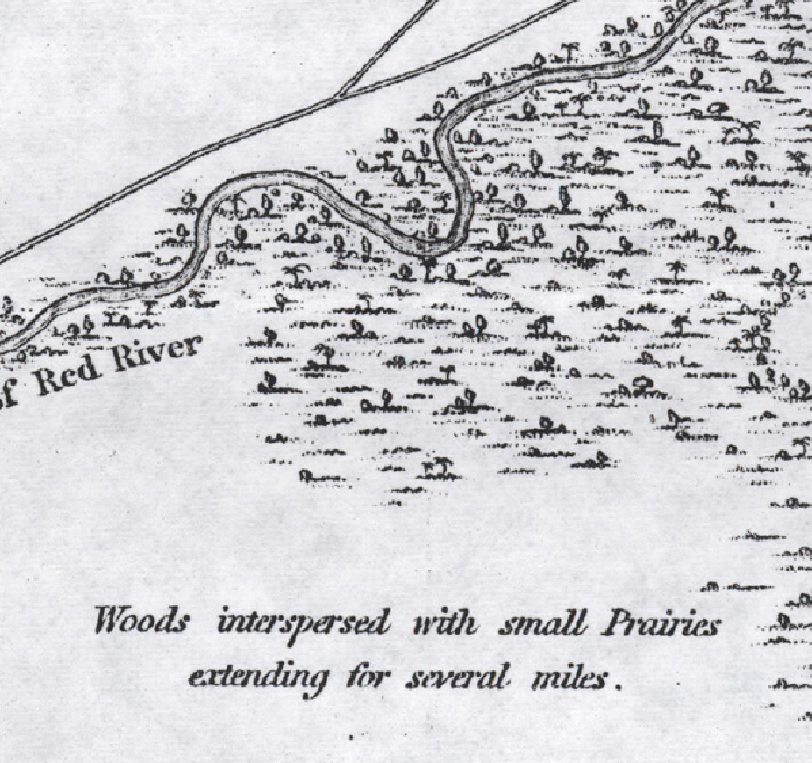

In 1984, Robert Michael W. Graham published his Master of Landscape Architecture thesis at the University of Manitoba, a project supported and inspired by landscape architect Garry Hilderman. Titled The Surface Waters of Winnipeg: Rivers, Streams, Ponds and Wetlands, 1874–1984, the practicum offers a detailed and critical account of the city’s evolving urban land drainage systems.

As part of his research, Graham includes depictions of the surface in the Contour Map of The City of Winnipeg. The map he draws from—originally produced in the early 1900s and updated in 1948—captures a layered history of the ground. Over millennia, the Assiniboine River gradually carved through the soft clay soils of the region, shaping the land’s grain to run from south to north before meeting the river. This geological shaping underpins both the physical and hydrological character of the Lot 908.

Contour Map of the City of Winnipeg,

A typical section reveals flood-tolerant shrubs—willow, maple, cottonwood—thriving along the river’s edge. Above the floodplain, Bur oaks and prairie grasses dominate drier, stable ground. This gradient reflects the interplay of seasonal flooding, soil conditions, and elevation, shaping a resilient and ecologically diverse riverbank landscape over time.

Vegetation in the Native Landscape.

In 1861, the Assiniboine River rose to a height of 32.5 feet, one of the most significant floods recorded in the region’s early settler history. The floodwaters spilled across the low-lying land, replenishing the floodplain with nutrient-rich silt and organic debris.

Nine years after the great flood of 1861, and shortly after Manitoba’s entry into Confederation in 1870, the Dominion government began systematic surveys of the region. These surveys redefined and reorganized the original Hudson’s Bay Company land holdings, dividing the large river lots into smaller, parish-based sections to accommodate new patterns of settlement and governance.

ESTATE (Lot 909 → Lot 42 → Lot H)

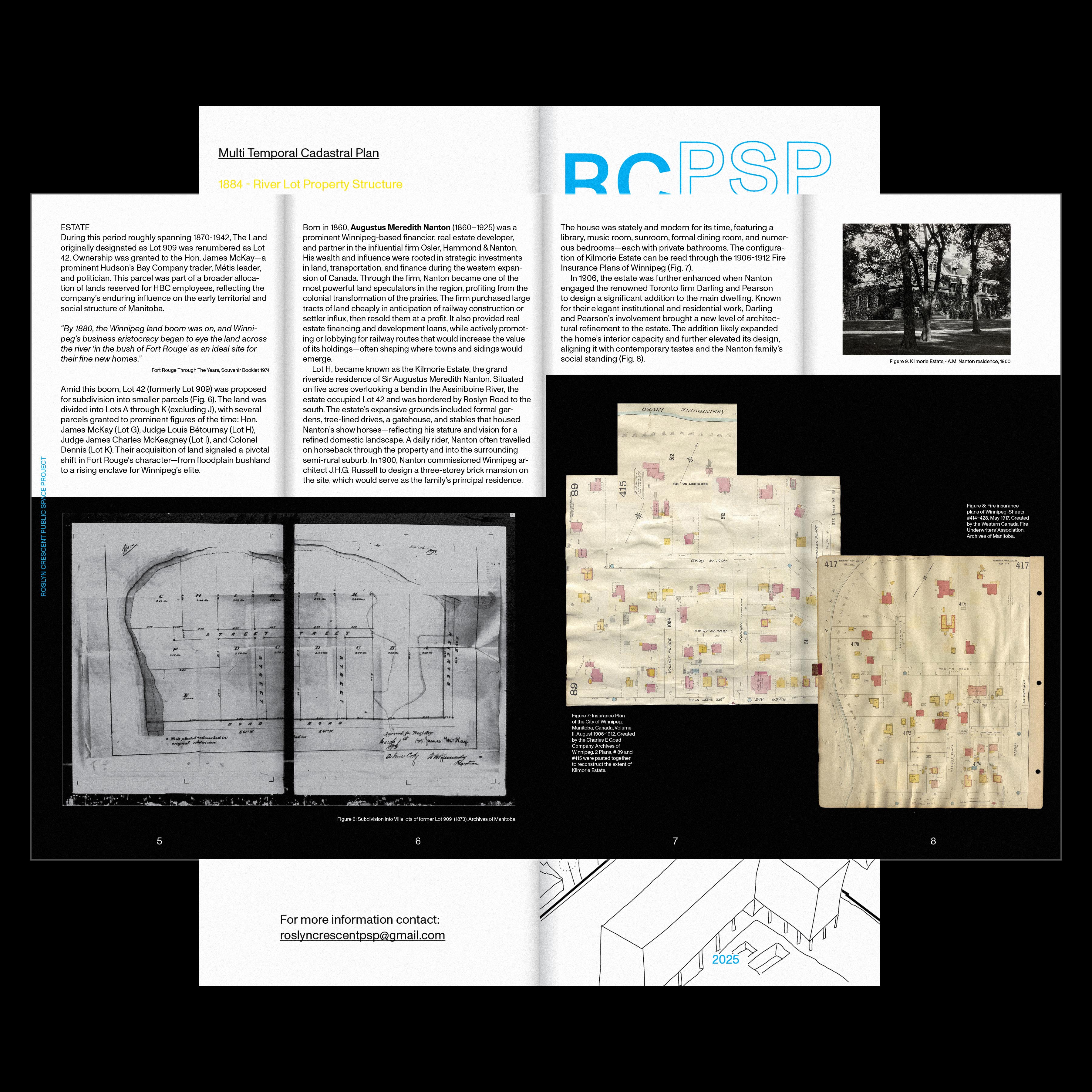

During this period roughly spanning 1870-1942, The Land originally designated as Lot 909 was renumbered as Lot 42. Ownership was granted to the Hon. James McKay—a prominent Hudson’s Bay Company trader, Métis leader, and politician. This parcel was part of a broader allocation of lands reserved for HBC employees, reflecting the company’s enduring influence on the early territorial and social structure of Manitoba.

“By 1880, the Winnipeg land boom was on, and Winnipeg’s business aristocracy began to eye the land across the river ‘in the bush of Fort Rouge’ as an ideal site for their fine new homes.”

Amid this boom, Lot 42 (formerly Lot 909) was proposed for subdivision into smaller parcels. The land was divided into Lots A through K (excluding J), with several parcels granted to prominent figures of the time: Hon. James McKay (Lot G), Judge Louis Bétournay (Lot H), Judge James Charles McKeagney (Lot I), and Colonel Dennis (Lot K). Their acquisition of land signaled a pivotal shift in Fort Rouge’s character—from floodplain bushland to a rising enclave for Winnipeg’s elite.

Born in 1860, Augustus Meredith Nanton (1860–1925) was a prominent Winnipeg-based financier, real estate developer, and partner in the influential firm Osler, Hammond & Nanton. His wealth and influence were rooted in strategic investments in land, transportation, and finance during the western expansion of Canada. Through the firm, Nanton became one of the most powerful land speculators in the region, profiting from the colonial transformation of the prairies. The firm purchased large tracts of land cheaply in anticipation of railway construction or settler influx, then resold them at a profit. It also provided real estate financing and development loans, while actively promoting or lobbying for railway routes that would increase the value of its holdings—often shaping where towns and sidings would emerge.

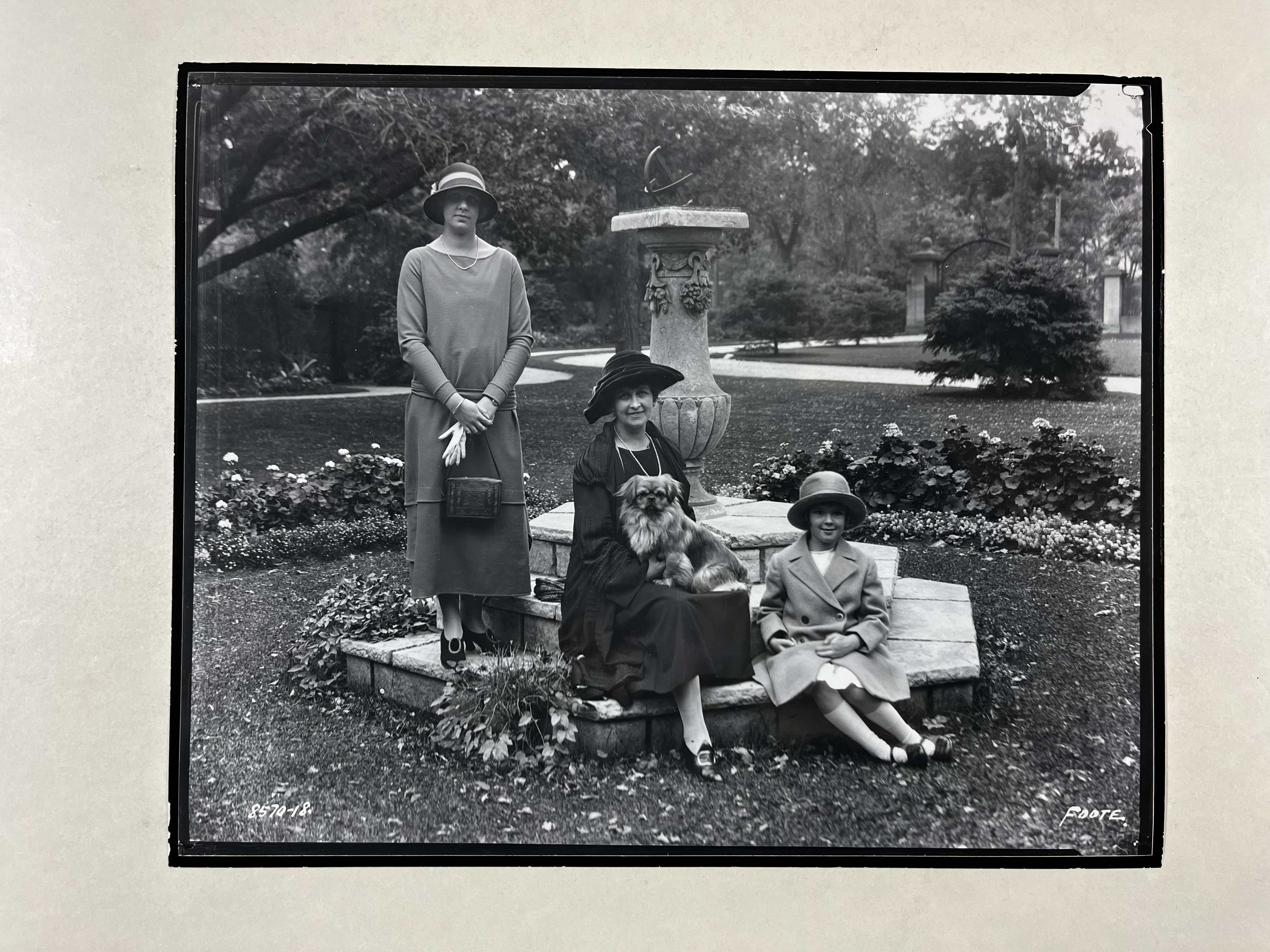

Lot H, became known as the Kilmorie Estate, the grand riverside residence of Sir Augustus Meredith Nanton. Situated on five acres overlooking a bend in the Assiniboine River, the estate occupied Lot 42 and was bordered by Roslyn Road to the south. The estate’s expansive grounds included formal gardens, tree-lined drives, a gatehouse, and stables that housed Nanton’s show horses—reflecting his stature and vision for a refined domestic landscape. A daily rider, Nanton often travelled on horseback through the property and into the surrounding semi-rural suburb.

Lot H, became known as the Kilmorie Estate, the grand riverside residence of Sir Augustus Meredith Nanton. Situated on five acres overlooking a bend in the Assiniboine River, the estate occupied Lot 42 and was bordered by Roslyn Road to the south. The estate’s expansive grounds included formal gardens, tree-lined drives, a gatehouse, and stables that housed Nanton’s show horses—reflecting his stature and vision for a refined domestic landscape. A daily rider, Nanton often travelled on horseback through the property and into the surrounding semi-rural suburb.

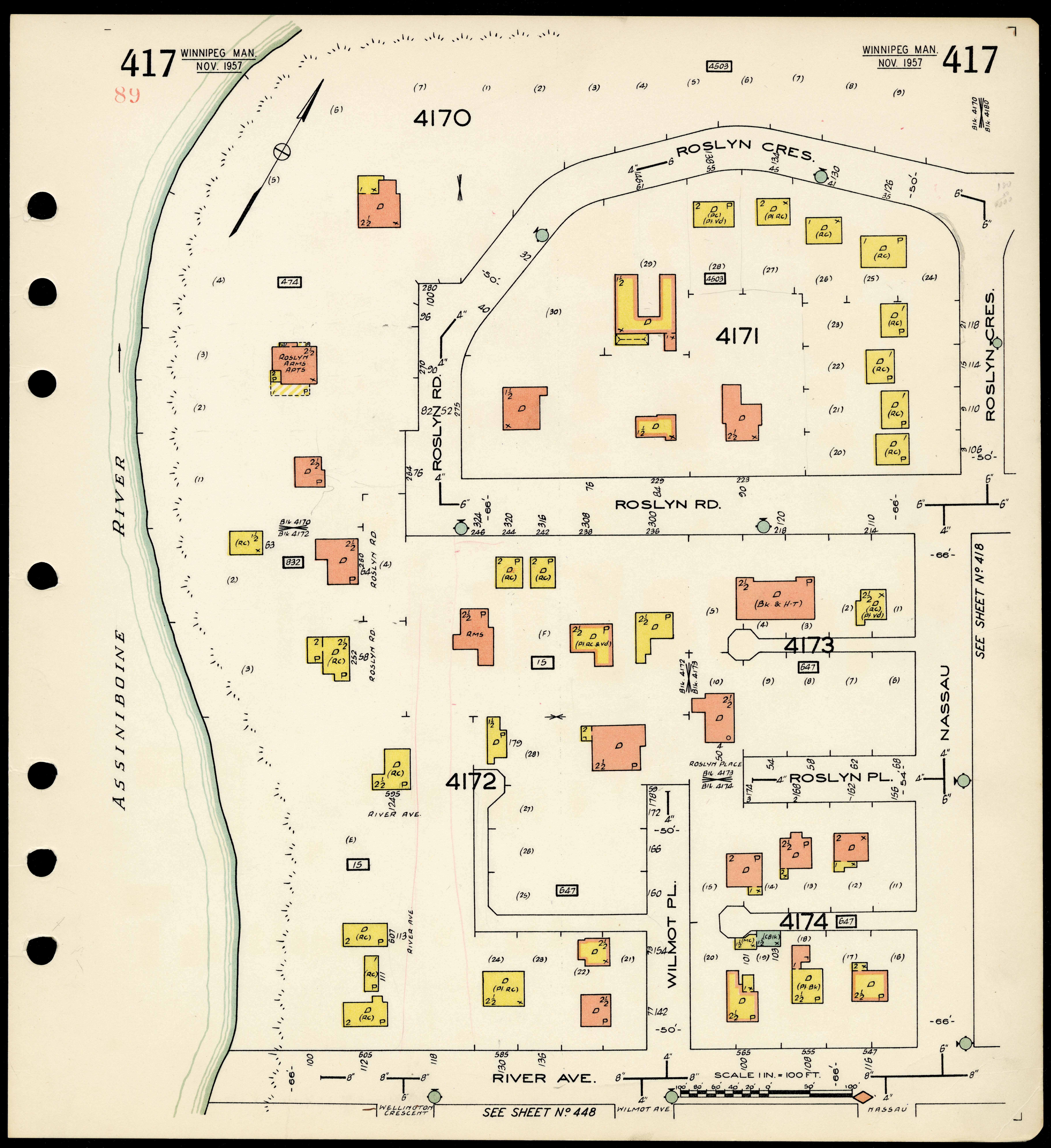

In 1900, Nanton commissioned Winnipeg architect J.H.G. Russell to design a three-storey brick mansion on the site, which would serve as the family’s principal residence. The house was stately and modern for its time, featuring a library, music room, sunroom, formal dining room, and numerous bedrooms—each with private bathrooms. The configuration of Kilmorie Estate can be read through the 1906-1912 Fire Insurance Plans of Winnipeg.

Insurance Plan of the City of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, Volume II, August 1906-1912. Created by the Charles E Goad Company. Archives of Winnipeg. 2 Plans, # 89 and #415 were pasted together to reconstruct the extent of Kilmorie Estate.

Insurance Plan of the City of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, Volume II, August 1906-1912. Created by the Charles E Goad Company. Archives of Winnipeg. 2 Plans, # 89 and #415 were pasted together to reconstruct the extent of Kilmorie Estate.

City of Winnipeg Archives - 229 Roslyn Building permit, 1900

In 1906, the estate was further enhanced when Nanton engaged the renowned Toronto firm Darling and Pearson to design a significant addition to the main dwelling. Known for their elegant institutional and residential work, Darling and Pearson’s involvement brought a new level of architectural refinement to the estate. The addition likely expanded the home’s interior capacity and further elevated its design, aligning it with contemporary tastes and the Nanton family’s social standing.

City of Winnipeg Archives - 229 Roslyn Building permit, 1906

GARDEN

Lot H, a subdivision of Block 42, appears to have undergone a selective clearing process as it was prepared for residential development. Rather than fully stripping the land, it seems the mature canopy trees—likely oaks and elms—were retained, while the dense understory of native shrubs and riparian bush was removed. The native understoryis replaced with a new aesthetic: the cultivated, orderly lawn.

This shift reflected broader trends of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when North American suburbs began to embrace the manicured residential garden as a symbol of refinement, control, and social aspiration. Frank J. Scott’s influential 1870 publication, The Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds, offers a valuable lens into this historical moment. His guide promoted the lawn not just as a decorative feature, but as a moral and cultural ideal—an embodiment of civilization, domestic order, and good taste.

Scott’s vision prioritized open lawns framed by ornamental trees and shrubs, discouraging wild or “unkempt” plantings. In this framework, native bushland was seen as something to be subdued or erased. The transformation of Lot H’s landscape was part of this larger movement: a rejection of the ecological messiness of the riverbank in favor of imported models of suburban beauty.

This clearing and landscaping fundamentally altered the ecological character of the Land. It eliminated the habitat complexity that had supported diverse plant and animal species, reduced the land’s natural capacity to absorb stormwater, and introduced maintenance practices—like mowing and watering—that continue to shape landscape maintenance practice in the area today.

Kilmore Estate - Lady Nanton(?), growing tomatoes

![]()

Following Sir Augustus’s death in 1925, the large estate became increasingly difficult for the family to maintain. The main house was demolished in 1935, but rather than abandon the property entirely, the gatehouse was renovated to serve as Lady Nanton’s residence. The renovation was undertaken by Moore and Moody Architects, a respected Winnipeg firm. They incorporated salvaged elements from the original mansion—such as oak paneling and the stone fireplace—preserving fragments of the estate’s former grandeur within the more modest structure. Lady Nanton lived there until her death in 1942

“After 1935, Herbert Moody of Moody Moore Architects renovated the former stable and transformed it into a single family dwelling for this family. To modify the stable, new windows and doors were cut into the brick veneer walls and additional dormers were added to the upper floor to create more living space. Robert Moore, business partner of Herbert Moody purchased the stable in 1940. Moore and his wife lived in the building unit 1972”

By 1946, the estate lots formerly known as Lots “H”, “I”, and “K” had been subdivided into residential parcels, each typically measuring 60 feet or wider. The 30 “new” lots were given the name “Roslyn Crescent”. Evidence of a real estate advertisement from May 1946 points to an active subdivision process and marketing campaign during that year. The ad promoted the availability of large, treed lots for residential development, signaling a shift in the neighborhood’s identity—from exclusive estate grounds to an upper-middle-class residential enclave. The subdivision activity also suggests that a key transfer of ownership likely occurred in the early 1940s, enabling the formal partitioning and sale of the lots. The marketing and sale of Roslyn Crescent was managed by C.E. Simonite Ltd., a prominent Winnipeg real estate firm led by Charles Edward Simonite, a former city alderman and long-time finance committee chair. Simonite played a notable role in shaping postwar urban development in Winnipeg, and his firm’s involvement in the subdivision underscores the growing demand for well-located residential land during the postwar housing boom.

“During the 1950 flood, residents of Roslyn Cresent were evacuated from their homes. 16 of the houses on Roslyn Crescent were flooded to the first floor. Most of them were only a few years old at the time. In recent years, many of the houses have been replaced or heavily modified”

After the devastating 1950 Red River flood, a federal-provincial task force titled the Red River Basin Investigation was established to study the causes and consequences of the disaster, and to propose long-term flood mitigation strategies. As part of this effort, the task force produced a series of detailed flood extent maps. The Greater Winnipeg Flooded Area map (Fig.14) clearly shows Roslyn Crescent as one of the heavily inundated areas, with floodwaters covering large portions of the newly established residential neighbourhood. The mapping work provided critical data that helped inform major infrastructure responses, including the design and construction of the Red River Floodway, aimed at protecting Winnipeg from future flooding events.

Title: Red River Floodway and Related Flood Control Works

Title: Red River Floodway and Related Flood Control WorksAuthor: Thomas E. Weber

Presented at: ASCE National Structural Engineering Meeting

Date: April 9–13, 1973

Location: San Francisco, California

Original Publication: Meeting Preprint (1966)

These flood control works, completed between 1968 and 1972, fundamentally reengineered the relationship between land and water in the Red and Assiniboine River basins. Where once the land was shaped annually by the swelling and recession of floodwaters—an ecological rhythm that defined settlement patterns, soil fertility, and vegetation cycles—it was now increasingly disassembled from these seasonal dynamics. The construction of the Red River Floodway, Portage Diversion, and Shellmouth Dam introduced a rigid hydrological regime designed to manage spring runoff and protect urban infrastructure. While these interventions successfully reduced flood risk and safeguarded Winnipeg, they also subdued the natural processes that had long defined the prairie landscape: periodic inundation, sediment deposition, and riparian renewal. As detailed in Thomas E. Weber’s 1973 engineering report, this new system could withstand a flood 60% greater than that of 1950, but in doing so, it redrew the ecological identity of the land, converting once-fluid floodplains into static zones of engineered control. What emerged was a territory shaped less by the watershed seasonal logic and more by the logic of infrastructure—one where rivers were no longer agents of renewal but objects to be managed, diverted, and contained.

URBAN GROWTH (Lot 23)

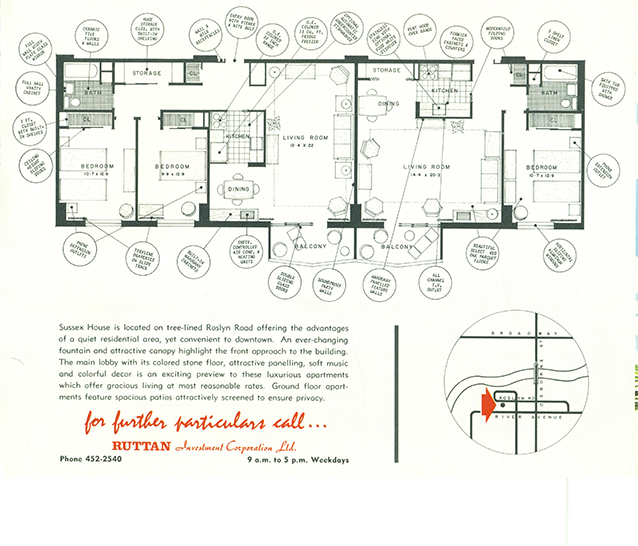

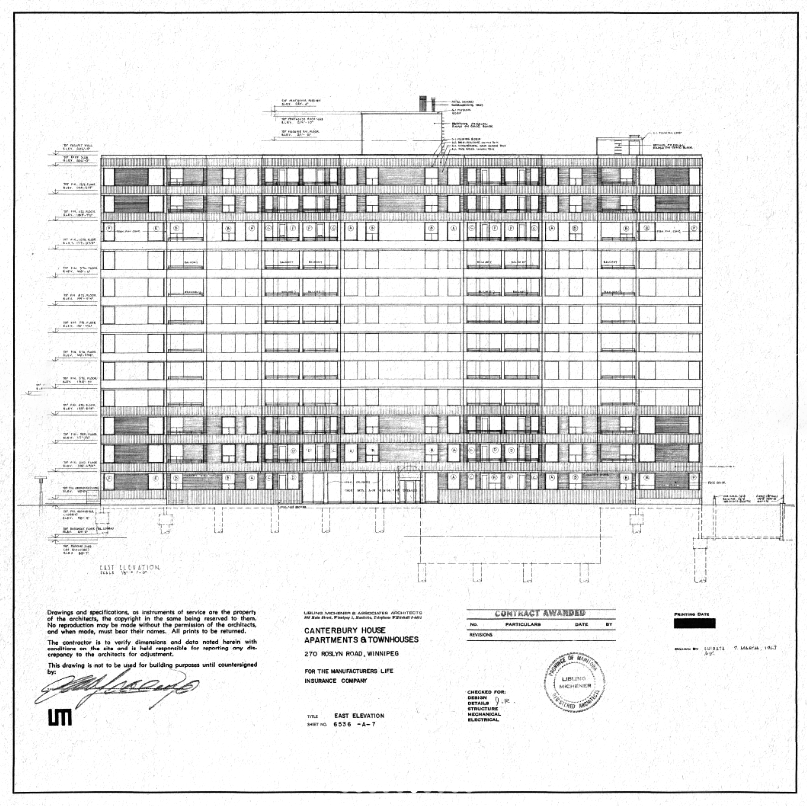

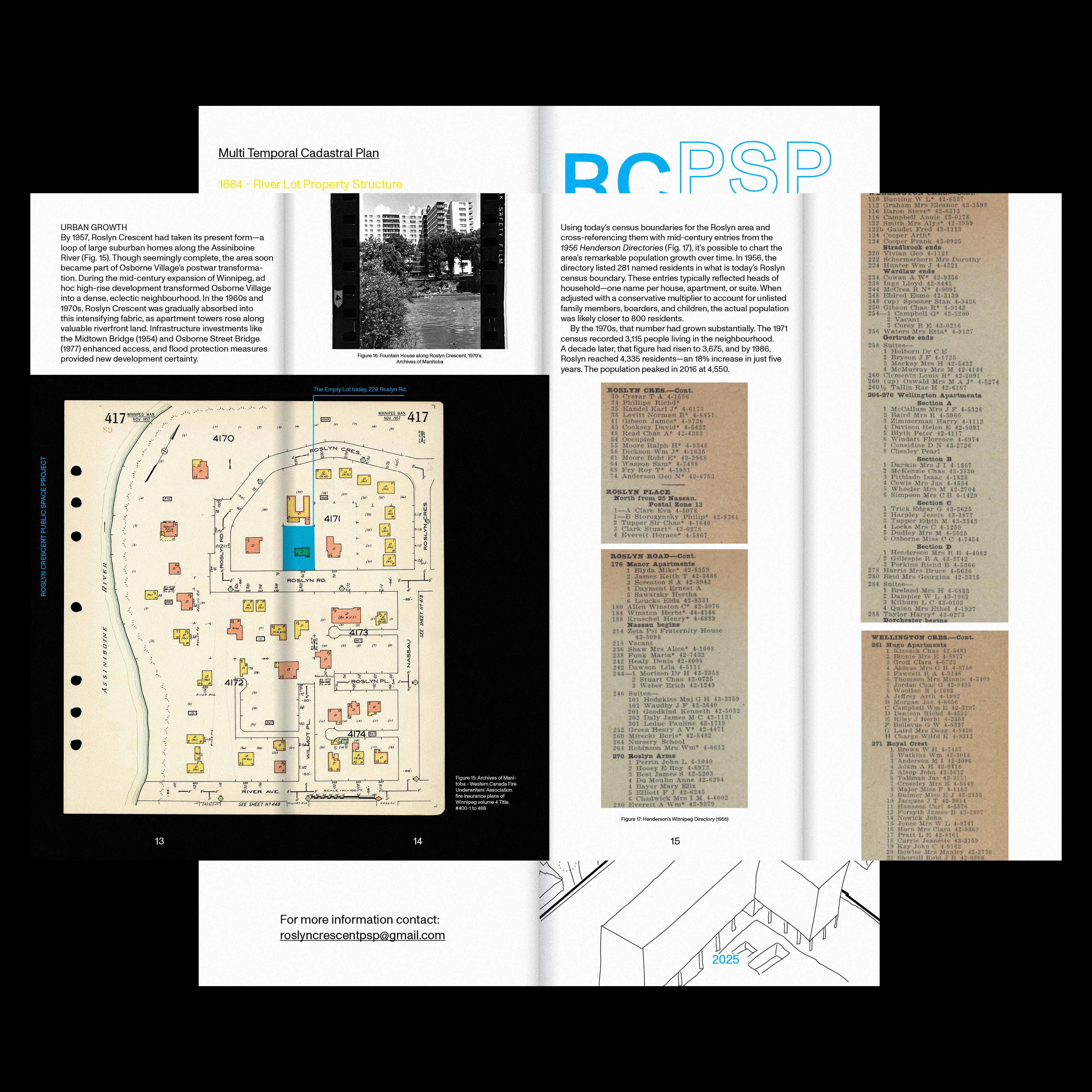

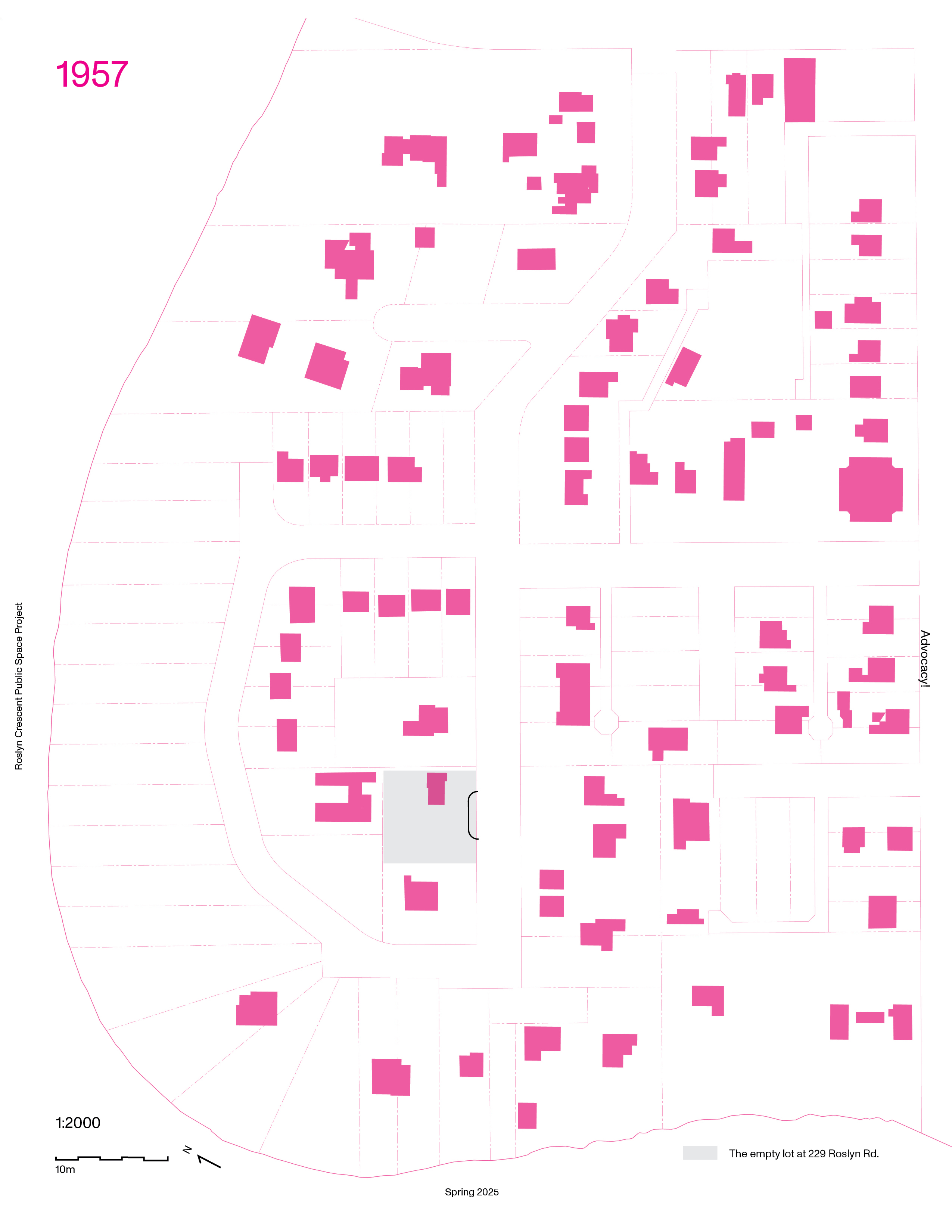

By 1957, Roslyn Crescent had taken its present form—a loop of large suburban homes along the Assiniboine River. Though seemingly complete, the area soon became part of Osborne Village’s postwar transformation. During the mid-century expansion of Winnipeg, ad hoc high-rise development transformed Osborne Village into a dense, eclectic neighbourhood. In the 1960s and 1970s, Roslyn Crescent was gradually absorbed into this intensifying fabric, as apartment towers rose along valuable riverfront land. Infrastructure investments like the Midtown Bridge (1954) and Osborne Street Bridge (1977) enhanced access, and flood protection measures provided new development certainty.

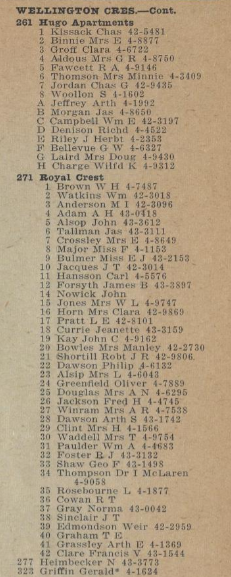

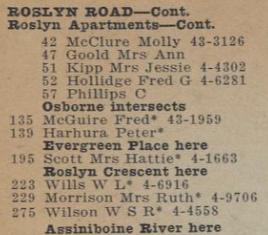

Using today’s census boundaries for the Roslyn area and cross-referencing them with mid-century entries from the 1956 Henderson Directories (Fig. 17), it’s possible to chart the area’s remarkable population growth over time. In 1956, the directory listed 281 named residents in what is today’s Roslyn census boundary. These entries typically reflected heads of household—one name per house, apartment, or suite. When adjusted with a conservative multiplier to account for unlisted family members, boarders, and children, the actual population was likely closer to 800 residents.

By the 1970s, that number had grown substantially. The 1971 census recorded 3,115 people living in the neighbourhood. A decade later, that figure had risen to 3,675, and by 1986, Roslyn reached 4,335 residents—an 18% increase in just five years. The population peaked in 2016 at 4,550.

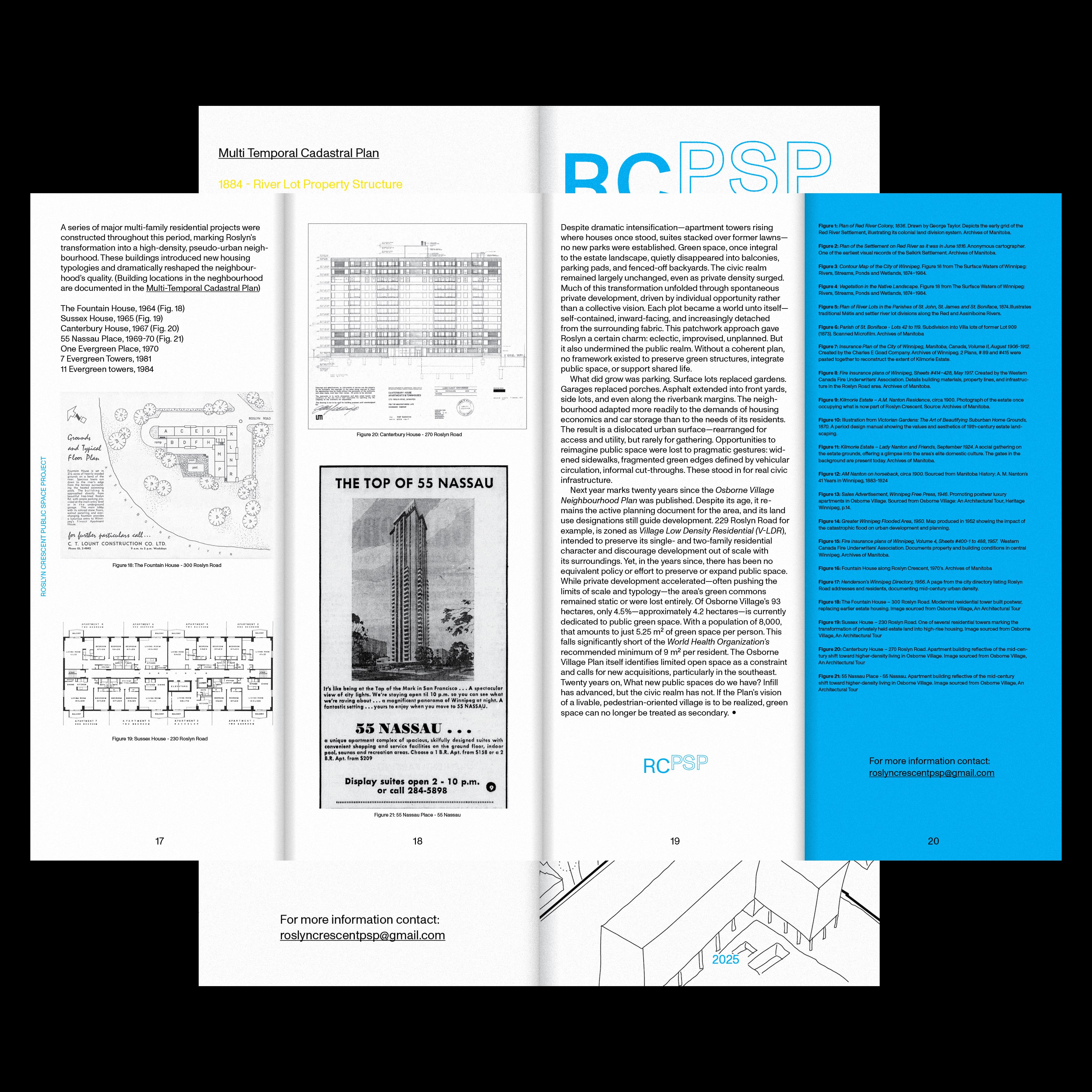

A series of major multi-family residential projects were constructed throughout this period, marking Roslyn’s transformation into a high-density, pseudo-urban neighbourhood. These buildings introduced new housing typologies and dramatically reshaped the neighbourhood’s quality.

A) The Fountain House, 1964

B) Sussex House, 1965

C) Canterbury House, 1967

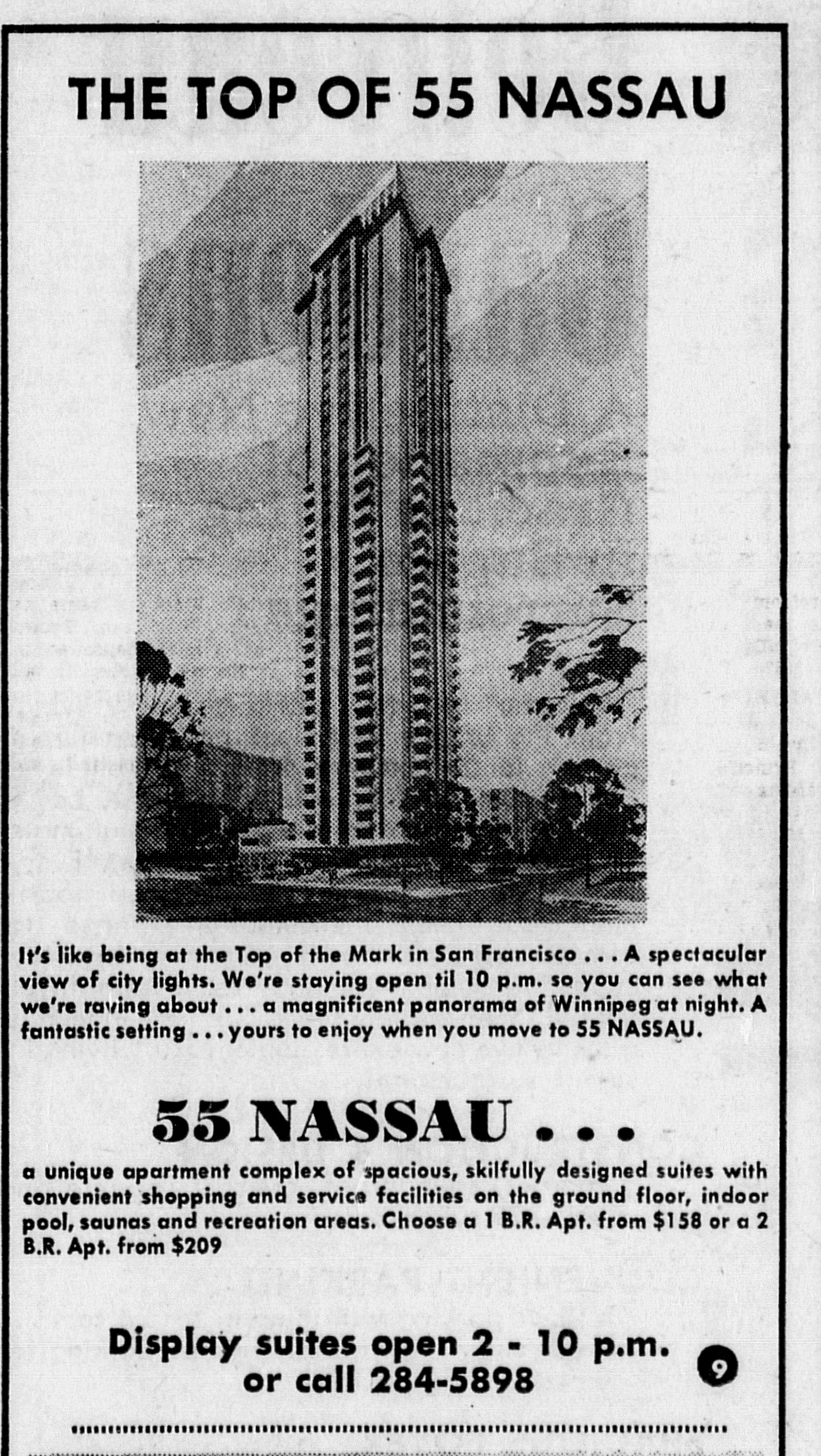

D) 55 Nassau Place, 1969-70

E) One Evergreen Place, 1970

F) 7 Evergreen Towers, 1981

G) 11 Evergreen towers, 1984

2025 Neighbourhood Plan

Despite dramatic intensification—apartment towers rising where houses once stood, suites stacked over former lawns—no new parks were established. Green space, once integral to the estate landscape, quietly disappeared into balconies, parking pads, and fenced-off backyards. The civic realm remained largely unchanged, even as private density surged. Much of this transformation unfolded through spontaneous private development, driven by individual opportunity rather than a collective vision. Each plot became a world unto itself—self-contained, inward-facing, and increasingly detached from the surrounding fabric. This patchwork approach gave Roslyn a certain charm: eclectic, improvised, unplanned. But it also undermined the public realm. Without a coherent plan, no framework existed to preserve green structures, integrate public space, or support shared life.

What did grow was parking. Surface lots replaced gardens. Garages replaced porches. Asphalt extended into front yards, side lots, and even along the riverbank margins. The neighbourhood adapted more readily to the demands of housing economics and car storage than to the needs of its residents. The result is a dislocated urban surface—rearranged for access and utility, but rarely for gathering. Opportunities to reimagine public space were lost to pragmatic gestures: widened sidewalks, fragmented green edges defined by vehicular circulation, informal cut-throughs. These stood in for real civic infrastructure.

Next year marks twenty years since the Osborne Village Neighbourhood Plan was published. Despite its age, it remains the active planning document for the area, and its land use designations still guide development. 229 Roslyn Road for example, is zoned as Village Low Density Residential (V-LDR), intended to preserve its single- and two-family residential character and discourage development out of scale with its surroundings. Yet, in the years since, there has been no equivalent policy or effort to preserve or expand public space. While private development accelerated—often pushing the limits of scale and typology—the area’s green commons remained static or were lost entirely. Of Osborne Village’s 93 hectares, only 4.5%—approximately 4.2 hectares—is currently dedicated to public green space. With a population of 8,000, that amounts to just 5.25 m² of green space per person. This falls significantly short of the World Health Organization’s recommended minimum of 9 m² per resident. The Osborne Village Plan itself identifies limited open space as a constraint and calls for new acquisitions, particularly in the southeast.

Next year marks twenty years since the Osborne Village Neighbourhood Plan was published. Despite its age, it remains the active planning document for the area, and its land use designations still guide development. 229 Roslyn Road for example, is zoned as Village Low Density Residential (V-LDR), intended to preserve its single- and two-family residential character and discourage development out of scale with its surroundings. Yet, in the years since, there has been no equivalent policy or effort to preserve or expand public space. While private development accelerated—often pushing the limits of scale and typology—the area’s green commons remained static or were lost entirely. Of Osborne Village’s 93 hectares, only 4.5%—approximately 4.2 hectares—is currently dedicated to public green space. With a population of 8,000, that amounts to just 5.25 m² of green space per person. This falls significantly short of the World Health Organization’s recommended minimum of 9 m² per resident. The Osborne Village Plan itself identifies limited open space as a constraint and calls for new acquisitions, particularly in the southeast.

Osborne Village Neighbourhood Plan - Parks and Open Space

Twenty years on, What new public spaces do we have? Infill has advanced, but the civic realm has not. If the Plan’s vision of a livable, pedestrian-oriented village is to be realized, green space can no longer be treated as secondary.

2025